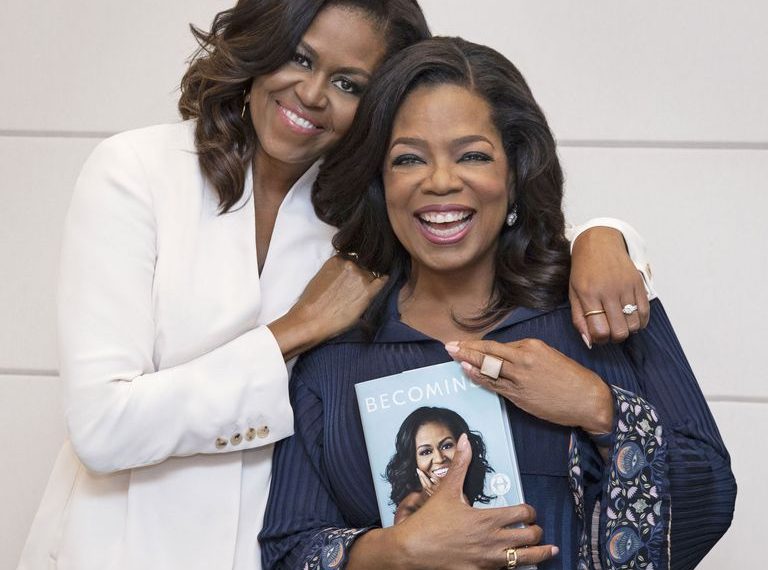

In a revealing interview, former first lady Michelle Obama—and author of the new memoir Becoming—opens up about marriage, life after the White House, and the truth she can finally say out loud.

An excerpt exclusively featured in Harpersbazaar.com Oprah by lines or rather shares the interview she had with the Former First Lady of America, Michelle Obama. Here is some of the conversation Oprah had with Mrs Obama:

“Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama doesn’t do a lot of interviews, and this was her very first time talking about her new memoir, Becoming (Crown). It is a remarkable book—I urge, urge, urge you to read it. Because I have known Mrs. Obama for 14 years, and I can tell you: She is everything you think she is and then some. She served as our country’s first lady with such dignity, such grace, such style. Yet at the same time, she really is just like all of us. I’m excited for you to see that about her, and to get to know her better and to catch up on what she’s been doing the past two years. So prepare to be fascinated. And to everyone who was in that room back in September: You can exhale now.

First, let me just say: Nothing makes me happier than sitting down with a good read. So when I realized—in the preface!—what an extraordinary book was coming, I was so proud of you. You landed it. The book is tender, it is compelling, it is powerful, it is raw.

Thanks.

Why Becoming?

We actually had a blooper list of titles that we won’t go into here. But Becoming just summed it all up. A question that adults ask kids—I think it’s the worst question in the world—is “What do you want to be when you grow up?” As if growing up is finite. As if you become something and that is all there is.

There are so many revelations in this book. Was writing about your private life scary?

Actually, no, because here’s the thing that I realized: People always ask me, “Why is it that you’re so authentic?” “How is it that people connect to you?” And I think it starts because I like me. I like my story and all the bumps and bruises. I think that’s what makes me uniquely me. So I’ve always been open with my staff, with young people, with my friends. And the other thing, Oprah: I know that whether we like it or not, Barack and I are role models.

I hate when people who are in the public eye—and even seek the public eye—want to step back and say,“Well, I’m not a role model. I don’t want that responsibility.” Too late. You are. Young people are looking at you. And I don’t want young people to look at me here and think, Well, she never had it rough. She never had challenges, she never had fears.

In reading the book, I can see how every single thing you’ve done in your life has prepared you for the moments and years ahead. I do believe this.

That’s if you think about it that way. If you view yourself as a serious person in the world, every decision that you make really does build to who you are going to become.

You mention this phrase that I like so much, I think it should be on a T-shirt or something. “Failure,” you say, “is a feeling long before it becomes an actual result. It’s vulnerability that breeds with self-doubt and then is escalated, often deliberately, by fear.” Failure is a feeling long before it becomes an actual result. You knew this when?

Oh, first grade. I could see my neighborhood changing around me. We moved there in the 1970s. We lived with my great-aunt in a very little apartment over a home she owned. She was a teacher, and my great-uncle was a Pullman porter, so they were able to purchase a home in what was then a predominantly white community. Our apartment was so small that what was probably the living room was divided up into three “rooms.” Two were me and my brother’s; each fit a twin bed, and it was just wood paneling that separated us—there was no real wall, we could talk right between us. Like, “Craig?” “Yep?” “I’m up. You up?” We would throw a sock over the paneling as a game.

You say your parents invested in you. They didn’t own their own home. They didn’t vacation—

They invested everything in us. My mom didn’t go to the hairdresser. She didn’t buy herself new clothes. My father was a shift worker. I could see my parents sacrificing for us.

Did you know at the time it was sacrifice?

Our parents didn’t guilt-trip us, but I had eyes, you know? I saw my father going to work in that uniform every day.

You write, about meeting him: “I’d constructed my existence carefully, tucking and folding every loose and disorderly bit of it, as if building some tight and airless piece of origami…. He was like a wind that threatened to unsettle everything.” At first you didn’t like being unsettled.

Oh God, no.

This I love so much—a moment that cracks me up: “I woke one night to find him staring at the ceiling, his profile lit by the glow of street lights outside. He looked vaguely troubled, as if he were pondering something deeply personal. Was it our relationship? The loss of his father? ‘Hey, what are you thinking about over there?’ I whispered. He turned to look at me, his smile a little sheepish. ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘I was just thinking about income inequality.’”

That’s my honey.

[Laughs]

I mean, here’s this guy and—at the time, I was a young professional. This is when I was coming into my own, right? I had a job that paid more than my parents ever made in their lives. I was rolling with bourgeois class.

Uh-huh.

My friends owned condos, I had a Saab. I don’t know what’s cool these days, but a Saab, back in the day—oh yeah. I had a Saab, and the next step was, okay, you get married, you have a lovely home, and on and on and on. Yes, the bigger problems of the world were important. But the more important thing was where you were going in your career. I talk about Barack meeting some of my friends and how that didn’t really play out.

You also write, “When it came down to it, I felt vulnerable when he [Barrack] was away.” I thought that was kind of amazing, to hear a modern woman—a first lady—admit that.

I feel vulnerable all the time. And I had to learn how to express that to my husband, to tap into those parts of me that missed him—and the sadness that came from that—so that he could understand. He didn’t understand distance in the same way. You know, he grew up without his mother in his life for most of his years, and he knew his mother loved him dearly, right? I always thought love was up close. Love is the dinner table, love is consistency, it is presence. So I had to share my vulnerability and also learn to love differently. It was an important part of my journey of becoming. Understanding how to become us.

What was so valuable to me—and I think will be for everyone else who reads the book—is that nothing really changed. You just changed your perception of what was happening. And that made you happier.

Yeah. And a lot of the reason I share this is because I know that people look to me and Barack as the ideal relationship. I know there’s #RelationshipGoals out there. But whoa, people, slow down—marriage is hard!

You even say you all argue differently.

Oh God, yes. I am like a lit match. It’s like, poof! And he wants to rationalize everything. So he had to learn how to give me, like, a couple minutes—or an hour—before he should even come in the room when he’s made me mad. And he has to understand that he can’t convince me out of my anger. That he can’t logic me into some other feeling.

So what was the argument, or the conversation, that got you to say yes to him running for the presidency? Because you mention in the book that every time someone would ask him, he’d say, “Well, it’s a family decision.” Which was code for “If Michelle says I can, I can.”

Imagine having that burden. Could he, should he, would he. That happened when he wanted to run for state Senate. And then he wanted to run for Congress. Then he was running for the U.S. Senate. I knew that Barack was a decent man. Smart as all get-out. But politics was ugly and nasty, and I didn’t know that my husband’s temperament would mesh with that. And I didn’t want to see him in that environment.

But then on the flip side, you see the world and the challenges that the world is facing. The longer you live and read the paper, you know that the problems are big and complicated. And I thought, Well, what person do I know who has the gifts that this man has? The gifts of decency, first and foremost, of empathy second, of high intellectual ability. This man reads and remembers everything, you know? Is articulate. Had worked in the community. And really passionately feels like “This is my responsibility.” How do you say no to that? So I had to take off my wife hat and put on my citizen hat.

So my question is, when the weight of the world is on his shoulders, and you’re the shoulders that he’s leaning on, how did you carry that? How do you carry that?

Trying to be the calm in his swerve. Doing what I was taught: You know, when the leaves are blowing and the wind is rough, being a steady trunk in his life. Family dinners. That was one of the things I brought into the White House—that strict code of You gotta catch up with us, dude. This is when we’re having dinner. Yes, you’re president, but you can bring

your butt from the Oval Office and sit down and talk to your children.

Because children bring solace. They let you turn your sights off the issues of the day and focus on saving the tigers. That was one of Malia’s primary goals; she advocated throughout his presidency to make sure the tigers were saved. And hearing about what happened with what school friend—you know, falling into other people’s lives. Immersing yourself in the reality and the beauty of your children and your family. Plus, on the East Wing side, our motto was, we have to do everything excellently. If we do something—because the first lady doesn’t have to do anything—

We were clear that what we were going to do was going to have impact and was going to be positive. The West Wing had enough going on; we wanted to be the happy side of the house. And we were. You’d have national security advisers coming over to brief me about something. They’d fall into my office—which was beautifully decorated, lots of flowers, and apples, and we were always laughing—and they’d sit down for a briefing and wouldn’t want to leave. “We’re done, gentlemen.” “We don’t wanna go back!”

You end the book by talking about what will last. And one of the things that has lasted with you, you say, is the sense of optimism: “I continue, too, to keep myself connected to a force that’s larger and more potent than any one election, or leader, or news story—and that’s optimism. For me, this is a form of faith, an antidote to fear.” Do you feel that same sense of optimism for our country? For who we are, as a nation, becoming?

Yes. We have to feel that optimism. For the kids. We’re setting the table for them, and we can’t hand them crap. We have to hand them hope. Progress isn’t made through fear. We’re experiencing that right now. Fear is the coward’s way of leadership. But kids are born into this world with a sense of hope and optimism. No matter where they’re from. Or how tough their stories are. They think they can be anything because we tell them that. So we have a responsibility to be optimistic. And to operate in the world in that way.

You feel optimistic for our country?

[Tears up] We have to be.

This story originally appeared in the December 2018 Issue of O.

From: Oprah Magazine US

Source and images from: www.harpersbazaar.com