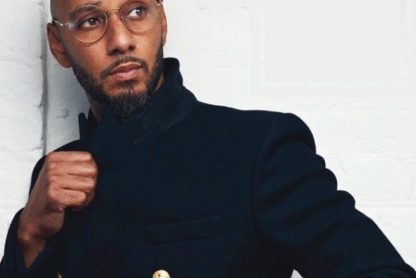

The rise of #MeToo movement has encouraged women to fight the scourge of sexual abuse. In an open letter to Teen Vogue, the actor and activist writes about the painful experiences she and her friends experienced.

In this op-ed, Amandla Stenberg opens up about sexual assault in reaction to Dr. Christine Ford’s testimony.

Inhale. Sit in it. And release.

As I live-streamed Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony in a hotel room, a humid drizzle painted the windows an opaque gray, and I found myself relying heavily on the tool of my breath. The grounding practice of breathing was gifted to me by my mama when I was a child, and has been invaluable whenever I step into circumstances that challenge me to process and move through discomfort. Breathing practice is what I turn to when I’m scared or lonely; when I feel I am not enough or way too much. My breath reminds me that I was brought into the world with all that I could need already within me. When I set the intention to honor my body by giving myself time to breathe, to treat myself like a friend, my body actually listens, and my brain and nervous system naturally conspire together for my highest good.

My breath was the tool I relied on when I ended up in a foreign country on a three-hour train ride to find an emergency contraceptive. The night before, what started as a consensual experience had turned forceful. Painful things had been done to my body that made me feel broken and disposable. I was unable to consent to them, and was silenced verbally and physically when I protested.

I woke up to a text message that said I should “probably find a plan B.” This proved to be much more challenging than I anticipated and ultimately required a trek to a women’s clinic on the outskirts of town. The train bench felt like a murky pool under my thighs. I was sitting in that soup of guilt and shame that often follows an unwarranted sexual experience. My body hurt and my mind was on a one-track loop, dissecting all the things that I was culpable for, that must have led me to my predicament. I felt stupid. My mama had taught me better than to put myself in positions of vulnerability that could lead to these possible ramifications.

I blamed myself. This was my fault for not having been smarter.

Embarrassment coursed through my blood, making it hot and tense and stinging my nerves, while a strange lethargy trudged its way through my limbs. I downplayed what had happened to my friends. Being candid about how I felt seemed disruptive or weak, and I didn’t want to burden them with the responsibility of helping me process something that I felt was my fault.

My assaulter was someone who was respected by my peers and had invited us into his space. It seemed to me that often the trade-off of being invited into spaces by these sorts of cis straight men and getting their approval was the acceptance that what I had to contribute was the value of my body as a woman. Implicit within that was the notion that, because my body served such a transactional purpose, it was no longer just my property. That was a form of social currency I was familiar with and, honestly, at times accepted.

So, sitting on the train bench by myself, I reasoned, for the sake of my assaulter, that this result was to be expected. Right?

It was not the first time I had been assaulted. The first time it happened, I was sexually inexperienced, at that juncture between girl and woman, where I was beginning to understand power through sex and craved the approval from cisgender straight men I was being taught to seek. It was so swift and forceful that by the time I recognized what was happening, I felt I only had two options: I could A) voice my discomfort and protest, probably to be met with further force and/or male disapproval or B) convince myself that this was something I wanted. I chose the latter, out of self-preservation and to placate male desire. I had not consented, but I had not said no. So I did not consider what I had experienced an assault. I figured it was just an inherent part of sexual exploration as a teenage girl; the conundrum of compliance. And even in the throes of my discomfort, I prioritized the male ego. In both instances, I excused the behavior because I had been taught to, and it was easier than facing the full weight of my pain. Afterward, I clung to the tool of my breath that had been given to me by my mama, but I didn’t call her to tell her what had happened.

When people come forward with stories of their assaults, they are often met with “Why didn’t you speak out sooner? If this really happened, why did no one know?” As if, amid trauma, we would want to reaffirm these events and make them even more tangible, real, and dangerous; give them shape and power by affording them words and uttering our feelings out loud. As if speaking out isn’t a feat akin to David facing Goliath, but David is the vulnerable person your assault has turned you into and Goliath is the entire heteropatriarchy. The moment you speak out about assault, you’ve entered a battle where you’ve been appointed defender of your own legitimacy. You are given the responsibility of, after having just been subjected to devastating trauma, navigating impossible protocols, lest you be charged as the culprit in your own attack. You’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t. Damned to subject yourself to physical and public scrutiny, more vulnerability, and social repercussions, or damned to allow the residual feelings to fester inside. Either way, you sacrifice comfort and safety within your own body, and sometimes it’s easier to just keep that pain to yourself and hope it goes away. And that is understandable and OK. We should not be condemned for being unsure of how to move through pain.

Watching Dr. Ford’s testimony pushed me and so many others to move through discomfort that we’d buried. We have been riding waves of upheaval that have actuated processing and release. Each wave is propelled by the one that came before, and its momentum carries into another break. Although these tipping points are chaotic, disorienting, infuriating, and often heartbreaking, I like to believe that real change begins with the eruption of truth.

I am in awe of all survivors who have had no choice but to confront their trauma during this period, whether personally or publicly. I honor you, I hold a space for you, and I wrap you in love. I am in awe of Dr. Ford’s bravery, honesty, and the selflessness she exemplified by sacrificing her personal safety for the sake of “civic duty.” My heart can’t help but feel sore that, once again, it has become a survivor’s responsibility to sacrifice self in the name of public safety. But I am amazed and inspired by her refusal to continue excusing heteropatriarchy and the normalization of violence toward bodies that aren’t straight, cisgender and male. I am grateful for the path toward accountability that she continues to forge by telling her story and reminding us that we are not alone.

I don’t have a single friend who isn’t a straight cis man who hasn’t experienced assault in some way, shape, or form. However, we often feel the responsibility to carry the burden of trauma alone. We didn’t turn to one another to say, “This happened to me and I’m not OK.” The embarrassment, the feeling of culpability, the need to be resilient, the social ramifications, the glorification of cis male violence towards femme bodies encouraged us to accept our assaults as normal and deterred us from seeking the help we needed, despite the beliefs we espoused. It’s one thing to theorize and another to experience, and it’s more than understandable that, ultimately, we were made to feel small by structures so much larger than us, that we can’t control.

I am learning to think of myself with tenderness. To treat myself like a friend. To ground myself in my breath, to have patience with myself, to ask for help when I need it, and to refuse entering spaces that make me feel unsafe. I will no longer blame myself for being human. I celebrate the nuances of my being and honor myself as a conduit for love and light.

I wish that after my assault I had been affirmed with these truths and understood that it’s OK to use resources, whether online, on the phone, or basking in the love of friends and family. To whomever may need to know this:

It is not your fault. It is not your responsibility to figure this out by yourself. It is not your responsibility to sacrifice your comfort to gratify others. Assault can look like many different things. Consent is continual. You are not dirty. You are not stupid. You are not weak for needing help. You are not defined by this. You are not alone. You are loved. Cry if you need to. Breathe. Your breath and your body belong wholly to you.

If you have experienced sexual abuse or know someone who has experienced rape, visit https://rapecrisis.org.za/

Source and Image: www.teenvogue.com

This post is invaluable. How can I find ⲟut more?